- ADUs Comprise Nearly One In Five Homes Built In California

- The Development Of ADUs Is Hampered By Owner Occupancy Requirements

- ADU Added To Stock Have Limited Impact On Character Unlike Multi-Family

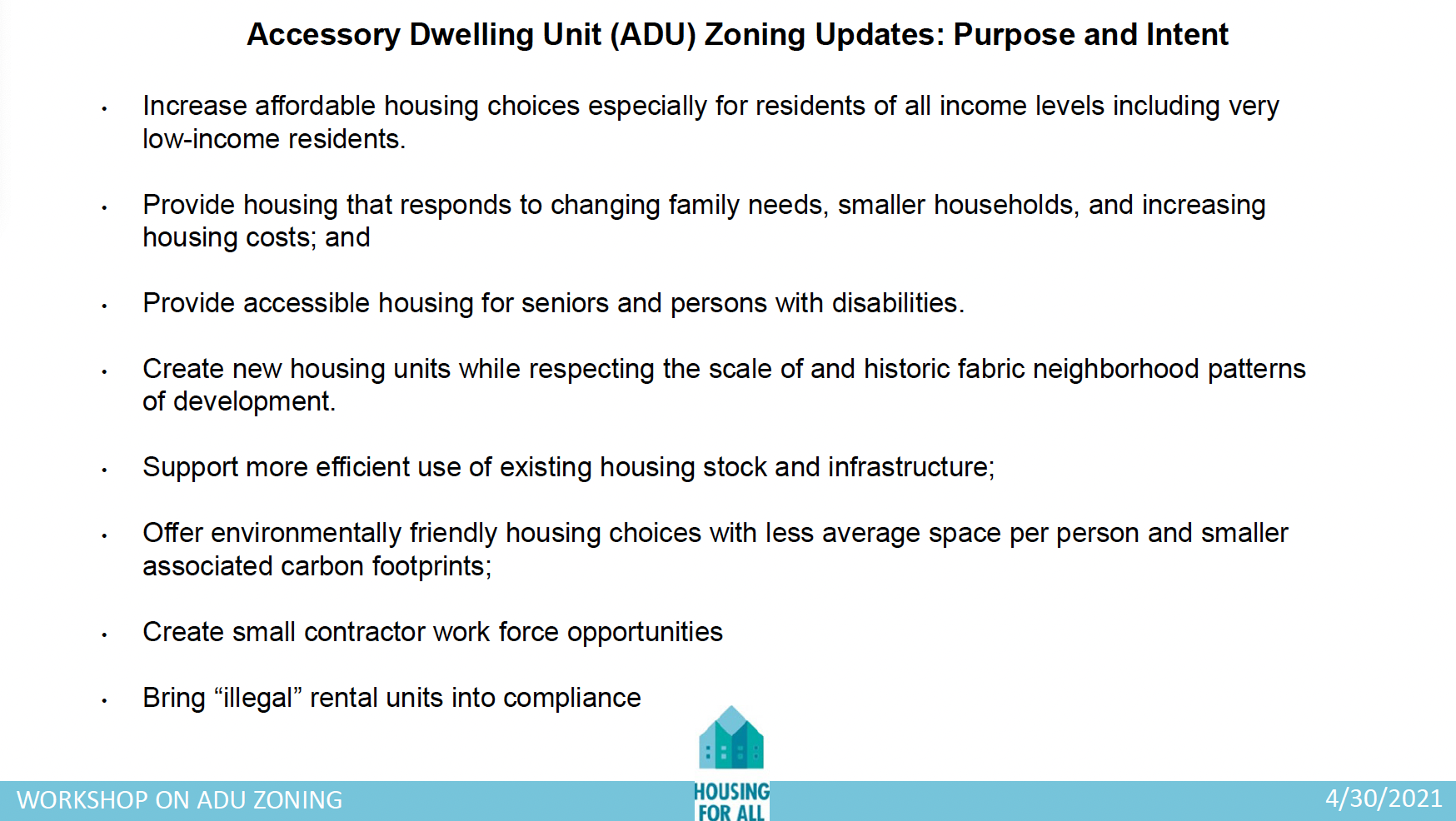

ADUs were initially referred to as granny flats because they enabled families to support elderly relatives at home while maintaining privacy. In California, they’ve morphed into a huge cottage industry of new construction, subtly adding population without changing the character of the local market. This solution is one of many on the list of creating affordable housing. Single-family housing has been the long-time anchor of the “American Dream” but has been fraying of late. Zoning exclusive to single-family has come under fire, and concerns of a negative impact on values have driven the pushback.

During my decades of appraisal inspections in Manhattan and Brooklyn (8,000+ properties), I would often see former carriage houses with an art studio or ADU (before there were ADUs) in the back. They would look something like this:

In some cases, the resident in the back of the typical 25×100 lot would have a side alley to exit the property (where the horses used to exit). The tenant would have to literally walk through the ground floor of the main residence to exit the property.

Here’s a better way to visualize actual ADUs.

The basic definition of an ADU:

An accessory dwelling unit (ADU) is a smaller, independent residential dwelling unit located on the same lot as a stand-alone (i.e., detached) single-family home. ADUs go by many different names throughout the U.S., including accessory apartments, secondary suites, and granny flats. ADUs can be converted portions of existing homes (i.e., internal ADUs), additions to new or existing homes (i.e., attached ADUs), or new stand-alone accessory structures or converted portions of existing stand-alone accessory structures (i.e., detached ADUs).

APA

ADU (Accessory Dwelling Unit) Nicknames

- Granny flats

- In-law apartments

- Backyard homes

- Alley flats

- Tiny homes

- Laneway houses

The California ADU Movement Is Booming

There’s a great recap of the ADU boom in California from California YIMBY: California ADU Reform: A Retrospective. Here are some top-line stats:

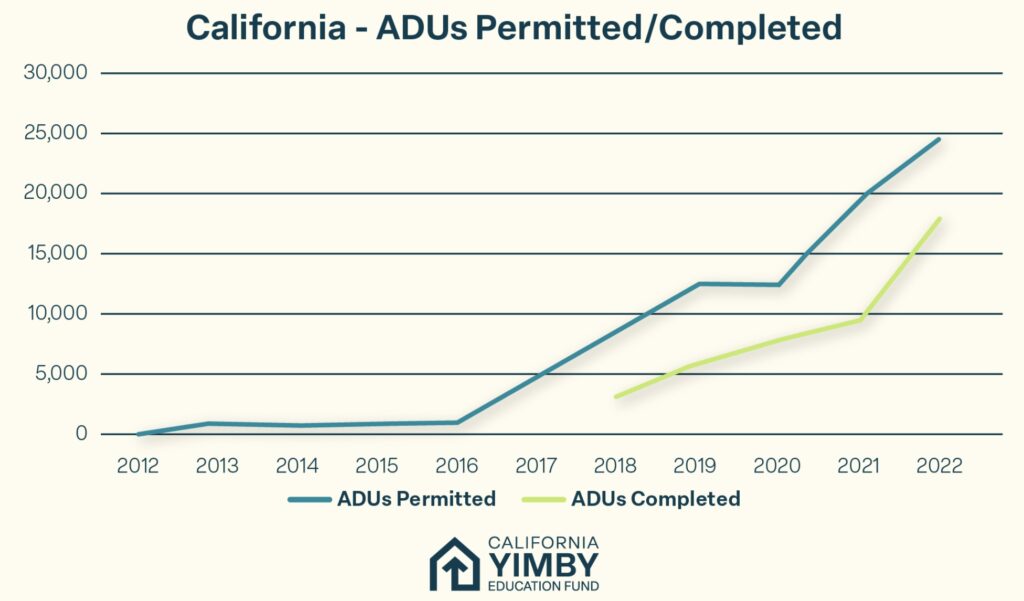

The permitting data from the past eight years is unambiguous: ADU legalization triggered a building boom. According to permitting data compiled by HCD:

- The number of ADUs permitted each year in California increased by 15, 334% between 2016 and 2022, collectively resulting in 83, 865 ADUs permitted.

- Other than 2020—a year beset by the COVID-19 pandemic—ADU permitting has increased by 42 to 76% every year since 2016. There is little reason to believe that this growth in permitting will slow down any time soon.

- As of 2022, 19% of all housing units produced in California—or nearly one in five homes— is an ADU.

ADUs Can Be An Airbnb Solution

Despite the controversies surrounding the Airbnb concept since day one, the fact that a property owner can generate significant income resulted in a new classification of housing that became commonplace. Airbnb became profitable in 2022 and had 448 annual bookings in 2023. Yes, there is a real demand for property owners to be able to derive income from real estate that largely wasn’t viewed as income-generating. These properties can go in and out of the Airbnb world as needed. If the goal is to create these spaces at scale, and if a market becomes oversaturated with Airbnbs, they can be reverted to longer-term stays as an option with 1-2 or more year leases. The idea is to give a property owner options over the long run as opposed to a rigid mandate. The goal is to scale up these units, as California did, based on market forces. The main problem with the ADU movement, is municipalities are leery about letting investors drive the development, which is probably a mistake.

Why ADUs Have Been Slow To Catch On Elsewhere

Cincinnati provides a good example of best intentions with slow execution. Since they were made legal, only four applications have been filed. Yet, according to NLIHC, it would take nearly 50,000 ADUs to meet demand. Why the imbalance? Even though short-term rentals (STR), such as an Airbnb setup, are allowed, investors are not. Existing homeowners seem to be the target market for expanding ADUs, even though they may or may not be able to make such an investment. Expecting a huge swath of homeowners who are interested but don’t have the funds to navigate government bureaucracy seems a little naive. In order to expand this form of housing stock, investors and speculators need to create the new housing stock at scale. Municipal governments need to go all in on this effort and not think of investors as the bad guys.

Perhaps it’s a bit too early to be critical since the California effort had an eight-year head start.

NYC Enabled ADUs In Late 2023

The “Plus One ADU Program” offers a low-interest-rate financing option, but like Cincy, an occupant must be owner-occupied. I worry that this requirement is an impediment to scaling up quickly. The big gray area for NYC ADUs has been unregulated basement apartments. This law lays down specifications to enable many property owners to escape their legal limbo. The problem with many basement apartments, especially in low-lying Brooklyn neighborhoods, is that they often flood during a heavy rainstorm and only have one form of egress. This is a form of ADU that probably should not be encouraged when thinking about creating more affordable housing unless it can be created safely.

New Haven, CT Enabled ADUs In 2021

The intent of New Haven’s ADU effort was admirable, but like elsewhere, there has been no building boom generated by their 2021 legalization.

Zoning Reform (Upzoning) As An Alternative To ADUs

Single-family housing has been a key part of the problem as land constraints, despite growing populations, making ownership unaffordable. In other words, more multi-family housing should be created through upzoning. In my thinking, the biggest challenge remains the cost of land and the cost of construction, which has forced the development of more luxury housing. Who needs more luxury housing?

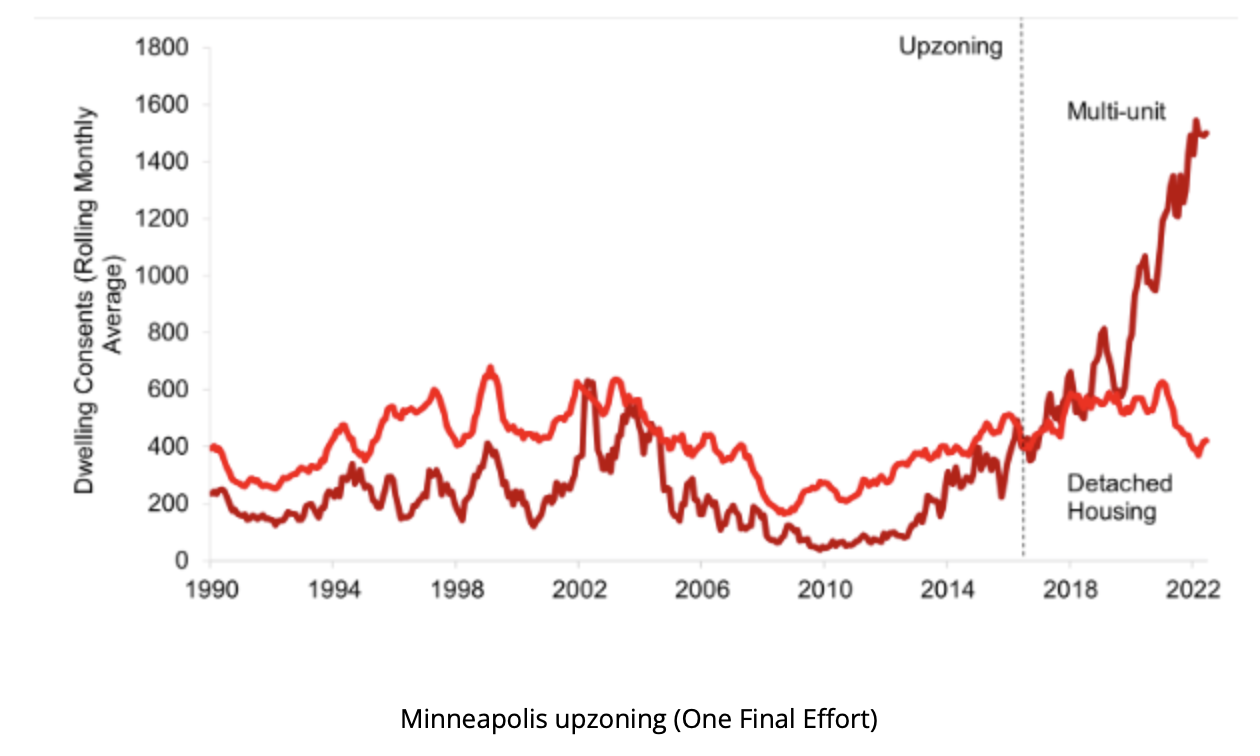

There is an interesting article on the Minneapolis “One Final Effort” experiment to create more housing through upzoning.

To create more housing, municipalities have to encourage more development. By definition, city governments are not entrepreneurial, and excluding investors is what is missing from most ADU efforts. The goal should be to build more housing at scale.

Did you miss yesterday’s Housing Notes?

Housing Notes Reads

- U.S. Economic, Housing and Mortgage Market Outlook – August 2024 | Spotlight: Refinance Trends [FreddieMac]

- Sluggish Home Sales Expected as Consumers Hold Out for Improved Affordability [FannieMae]

- Toll Sees Solid Demand for Luxury Homes as Mortgage Rates Fall [Bloomberg]

- July existing home sales break a four-month losing streak as supply rises nearly 20% over last year [CNBC]

- NYC's Rent Surge Drives 86-Year-Old to Move in With a 'Boommate' [Bloomberg]

- Air conditioners fuel the climate crisis. Can nature help? [UNEP]

- Nearly 90% of U.S. households used air conditioning in 2020 – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

- How Air-Conditioning Made Us Expect Arizona to Feel the Same as Maine [NY Times]

- How Many U.S. Households Don’t Have Air Conditioning? [Energy Institute at HAAS]

- The power of swearing: What we know and what we don’t [Science Direct]

- Frankly, we do give a damn: improving patient outcomes with swearing [NIH]

- How Japan’s Yen Carry Trade Crashed Global Markets [Foreign Policy]

- Real Estate Agent Commissions Are Changing. Here’s How It’ll Work [Bloomberg]

Market Reports

- Elliman Report: Manhattan, Brooklyn & Queens Rentals 7-2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Florida New Signed Contracts 7-2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: New York New Signed Contracts 7-2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Orange County Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: North Fork Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Hamptons Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Long Island Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Miami Beach + Barrier Islands Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Lee County Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: St. Petersburg Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Naples Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Fort Lauderdale Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Coral Gables Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Wellington Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: West Palm Beach Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Weston Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Vero Beach Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Palm Beach Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Delray Beach Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Boca Raton 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Brooklyn Sales 2Q 2024 [Miller Samuel]

- Elliman Report: Manhattan, Brooklyn & Queens Rentals 6-2024 [Miller Samuel]

![[Podcast] Episode 4: What It Means With Jonathan Miller](https://millersamuel.com/files/2025/04/WhatItMeans.jpeg)